It’s 2023, and despite all we know about the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), it remains the number one cause of death globally. Unlike diseases such as cancer and dementia, which often have no advance indicators, heart disease has early warning signs in the form of specific blood particles that, when elevated, tell us clearly that atherosclerosis is building.

While there are many risk factors for ASCVD, including smoking and high blood pressure, the measurement and treatment of these elevated blood particles is our best tool to stop unnecessary deaths from this entirely preventable disease. My own dad suffered a heart attack in his early 40s. This simply shouldn’t happen today.

The blood particles I’m referring to are lipoproteins, which are protein carriers of fat and cholesterol in the bloodstream. A subset of lipoproteins known as ApoB-containing lipoproteins are highly atherogenic, meaning they are the primary culprits in the development of atherosclerosis.

Each ApoB-containing lipoprotein carries a single ApoB protein called Apolipoprotein B-48 or B-100. This water-soluble ApoB protein transports fats and cholesterol, which are water-insoluble, through plasma. ApoB proteins are evolutions way of solving a problem – getting energy in the form of triglycerides, which are unable to travel freely in the blood, to the cells that need them.

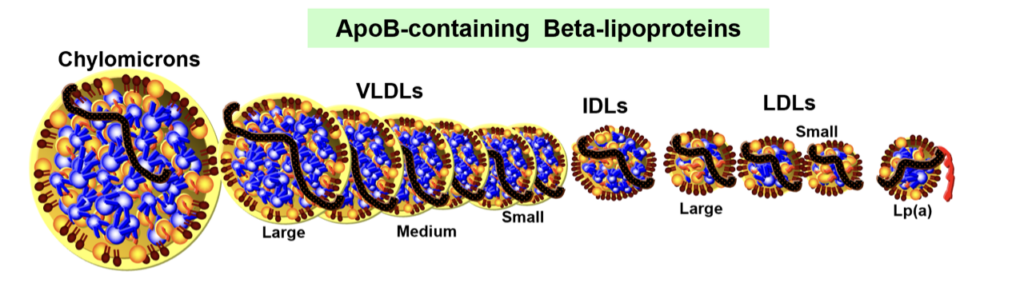

There are several types of ApoB-containing lipoproteins, including chylomicrons, chylomicron remnants, VLDL’s, IDL’s and LDL’s (see the chart below). LDLs typically account for 95% of these lipoproteins because, compared to other ApoB lipoproteins, they circulate the longest in plasma.

We now know that ApoB proteins are ‘sticky,’ meaning they have a high affinity for binding with proteoglycans, a protein compound found in the walls of arteries. When ApoB sticks to proteoglycans, the particles become retained or ‘stuck’ in the artery wall.

Due to their residence time, it’s primarily LDLs (low-density lipoproteins) that end up entering the artery wall, becoming retained after binding to proteoglycans and kickstarting an inflammatory cascade that ultimately leads to the development of fatty plaques (atherosclerosis).

Observational, clinical trial, and genetic data show a clear direct and causal relationship between ApoB levels and cardiovascular disease (CVD). The higher the ApoB level, the higher the risk of CVD. In contrast, at normal human physiologic levels (LDL-C of 20-40mg/dl), atherosclerosis does not occur, clear proof that elevated ApoB is a requirement for atherosclerosis.

The importance of ApoB as a predictor of CVD risk is accepted by the overwhelming majority of clinicians and academics in the cardiology field. Recent cardiology guidelines even address ApoB explicitly. However, certain circles continue to disregard the evidence. Many proponents of low carbohydrate or ketogenic diets question whether elevated ApoB is always a problem. It’s important to note that this is contrary to the views of the fathers of the paleo movement, including Loren Cordain and Stanley Boyd Eaton.

The dilemma for many following a low-carb ketogenic diet is twofold:

1 – To achieve a physiologic ApoB level through lifestyle alone, most people will have to make large dietary changes, especially those following a typical ketogenic diet. The biggest dietary culprits of elevated ApoB are:

- Saturated fats

- Refined carbohydrates

- Dietary cholesterol for the about 20% of people who are hyper absorbers of cholesterol

At a food level, decreasing ApoB requires eating fewer fatty cuts of meat, butter, high-carb ultra-processed foods, and to a lesser extent, minimally processed full-fat dairy (for reasons beyond the scope of this blog, the saturated fats in unrefined dairy foods have less effect on ApoB than those found in meat and butter).

An ApoB-lowering diet emphasises fatty fish, legumes and other plant protein, olive oil, and minimally processed fibre-rich sources of carbohydrates such as whole grains. A helpful resource for achieving a reduction in ApoB through nutrition is the Dietary Portfolio which has been shown to lower LDL-C by an average of 28% (similar to low-intensity statins).1 My n=1 anecdote, for what it’s worth, is that I was able to reduce my LDL-C from 120 mg/dl to 70-80 mg/dl with these sorts of dietary swaps.

Now, for the typical person following a ketogenic diet, achieving an optimal ApoB will mean giving up, or at least dramatically reducing, the foods that are often a staple part of their diet, such as beef, lamb, pork, butter, and cheese. It’s easy to see how a ketogenic diet without fatty meat and high-fat dairy would be a struggle.

2 – A large percentage of people will be unlikely to achieve an ApoB of < 50mg/dl with diet alone, even if the dietary changes were ‘perfected.’ There are a myriad of genes that affect serum cholesterol levels. Some of the major players that result in genetically elevated ApoB include:

- Genes that upregulate the PCSK9 gene. PCSK9 is an enzyme that degrades LDL receptors, the proteins that pull LDL out of the bloodstream. People with more PCSK9 have fewer LDL receptors and consequently, higher LDL in their blood.

- Genes that increase cholesterol absorption in the gut via the NPC1L1 and/or G5/G8 receptors. These people will most certainly require pharmacotherapy like statins, ezetimibe, bempedoic acid, or PCSK9 inhibitors to reach a physiologic ApoB level.

So if someone has elevated ApoB, what should they do? Here’s what I think the research supports:

- Find a diet that allows you to maintain a healthy body weight and body composition. (low carb, mod carb, or high carb). For some people, this will be a ketogenic diet. For others, it won’t. Done right, a low-carb, moderate-carb, or even high-carb diet can promote a healthy weight.

- Regardless of the carbohydrate composition of your diet, choose foods low in saturated fat, minimally processed, high in fibre, and plant-rich. This is possible on a low-carb diet, though in my experience, more challenging.

- If you can’t reach an optimal ApoB with diet alone, ask your doctor about pharmacotherapy with a minimum effective dose mindset.2 The goal is to achieve an optimal ApoB at the lowest level of medication possible. My rationale for a minimum dose mindset is based primarily on risk. If I can get all of my key health indicators into the optimal range while minimising the chance of side effects from pharmacotherapy, I think that’s a good outcome.

Ok, with all these recommendations in mind, I want to talk about the title of this article and this tweet, both written in jest, after being sent a podcast where Peter Attia talks with Andrew Huberman about taking a PCSK9 inhibitor and enjoying their steak. Admittedly, Peter didn’t mention fatty steak, but I did get the feeling from this conversation and this one with Rich Roll (both of which I greatly enjoyed) that he would rather use pharmacotherapy to optimise his lipids than limit saturated fats.

Fatty steaks with a statin and/or PCSK9 inhibitor. Somehow I think this could be a trend in 2023. Better than fatty steaks with elevated ApoB.

— Simon Hill MSc, BSc (Hons) (@theproof) March 25, 2023

Is this health optimisation?

While everyone’s approach to creating a sustainable diet and managing risk is different, I think this idea raises some interesting questions.

For one thing, could there be other reasons a diet high in red meat might be unwise? Our dietary choices don’t just influence ApoB and cardiovascular disease risk. There’s also a wealth of evidence linking high red meat and processed meat consumption to colorectal cancer. This doesn’t mean you can never have a steak, but when studies compare those who eat the lowest amounts of red meat and those who eat the highest, and there is sufficient contrast between these levels of intake, the risk of colorectal cancer is definitely increased. The same holds true for breast cancer.

Additionally, what risks are associated with cholesterol-lowering medication? Thankfully, most of these drugs are well-tolerated, but there are those who may experience side effects. This is a risk with any type of medication and should not be used as an excuse not to address high ApoB. But, as I mentioned before, using the lowest effective dose is a good mindset for exactly this reason. So, if you’re taking medication but not addressing the diet piece, you may end up unnecessarily needing a higher dose.

I’m not here to say that people can’t ever eat steak. While that is my chosen path based on the best available evidence, everyone has to decide for themselves. In small amounts, it likely won’t impact your risk of disease. But, I do feel the need to call out the mindset that we can rely on medication to fix the problems caused by our diet.

There are many good questions and some misinformation out there on this topic. I address a lot of this with Dr. Thomas Dayspring in our 3 part lipid series. I highly recommend you take the time to listen for an in-depth discussion of the mechanism, prevention, and treatment of CVD.

I truly do think that many dietary patterns can be health-promoting when done well. However, we can’t turn a blind eye to the preponderance of evidence pointing to the benefits of plant-based diets versus the risks of diets high in red meat and saturated fat. Cardiovascular disease is highly preventable, and no one should lose a loved one or suffer themselves when we know exactly what to do to lower risk.

1 The dietary portfolio also features plant sterol supplements. If you are going to take (or are taking) these, it would be wise to first test your sitosterol and campesterol levels. These are two phytosterols that certain laboratories, like EmpowerDX in the USA, can test for. If you commence supplementation, and these are markedly elevated, you should discontinue use. This is something I discuss with Dr. Thomas Dayspring in Part 3 of the lipid series.

2 In my discussions with Dr. Thomas Dayspring, he mentioned that <80 mg/dl is probably ok for someone who has a low risk of CVD, but anyone else should target < 50 mg/dl.