Dehydration can flatline exercise performance. Yet, all kinds of myths abound about the best way to get the fluid your body needs to fuel workout gains. It can be hard to cut through the noise and get to the actual science to guide our hydration choices.

Hydration is all about replenishment. Exercise leads to the depletion of fluid, electrolytes, and fuel as the body dips into stores to meet the higher demands and excretes fluid and electrolytes in sweat. Losing as little as 2% of total body weight can (1):

- Reduce cardiac output

- Impair blood flow to muscles

- Increase perceived exertion

- Decrease endurance

- Disrupt temperature regulation

Replacing these losses both during and after intense exercise is necessary to allow you to perform at a high level and make consistent gains.

In episode #259 of The Proof podcast, I spoke with Stacy Sims, PhD, an internationally renowned exercise physiologist and nutrition scientist who sheds light on how our bodies are designed to be hydrated. If you missed the episode, definitely have a listen. Her insight and expertise is invaluable.

To understand hydration, you need to know what is happening in the small intestine. This is where the majority of fluid absorption occurs. When you drink fluids, they pass through to the stomach, which can’t absorb much due to its thick mucous barrier, and then on to the small intestine.

The small intestine is relatively impermeable to water and water-soluble solutes. Water doesn’t just flow on its own from the intestine into the bloodstream. It requires a transport mechanism to essentially open the doors. In the small intestine, water absorption is facilitated by other solutes, primarily glucose and sodium.

When glucose and/or sodium activate a transport, water is passively pulled with it along the concentration gradient it creates. (2) It makes sense if you remember learning about osmosis in school. If not, here’s a handy visual that likely transports you back to your early days.

Source: Openstax

Glucose and sodium play a significant role in moving water from the small intestine (technically “outside” the body) to the bloodstream for hydration.

But contrary to popular belief, this does not make commercial sports drinks the right choice.

The amount of sugar and salt you need to optimize water absorption is fairly minimal. A hypotonic solution, meaning one with a relatively low concentration of solutes (in this case, sugar and salt), promotes the movement of water from the intestines to the bloodstream. (1) As a beverage becomes more concentrated, water absorption actually declines. (3)

Under sweaty exercise conditions, the body diverts energy away from digestion to supply working muscles and regulate temperature. (4) When there is less focus on digestion, the need for an assist from glucose and sodium increases. If you perform an intense, sweaty workout and lose a lot of water and salt, you may benefit from a small amount of sugar and a small amount of salt in your rehydration fluid to activate the transport systems that quickly pull water across the intestinal barrier and into the bloodstream.

If you look at the label on most sports drinks or rehydration fluids, you’ll find they often contain way more sugar and salt than you need. In many cases, the drinks are targeted at resupplying energy, not just fluids, but those two goals can be contradictory. Drinking a concentrated solution to get more energy provides too much volume for the small intestine to process quickly and may work against optimal water absorption.

While Dr. Sims caveats her guidance with the need to individualize, she does offer this recommendation for the average person exercising under reasonable conditions (i.e., not too hot or dry).

- A 1-3% concentration of a sucrose-containing beverage. 1 tsp (5 g) of maple syrup in 500 ml (2 cups) of water works.

- A small addition of salt. 1/16th of a tsp in 500 ml (2 cups) of water which is a small sprinkling (~145 mg of sodium).[1]

- An hour before your workout, drink 500 ml (2 cups) of this solution to ensure you are hydrated.

- Sip more of this solution throughout your workout, setting a timer if needed to remind yourself to have a drink.

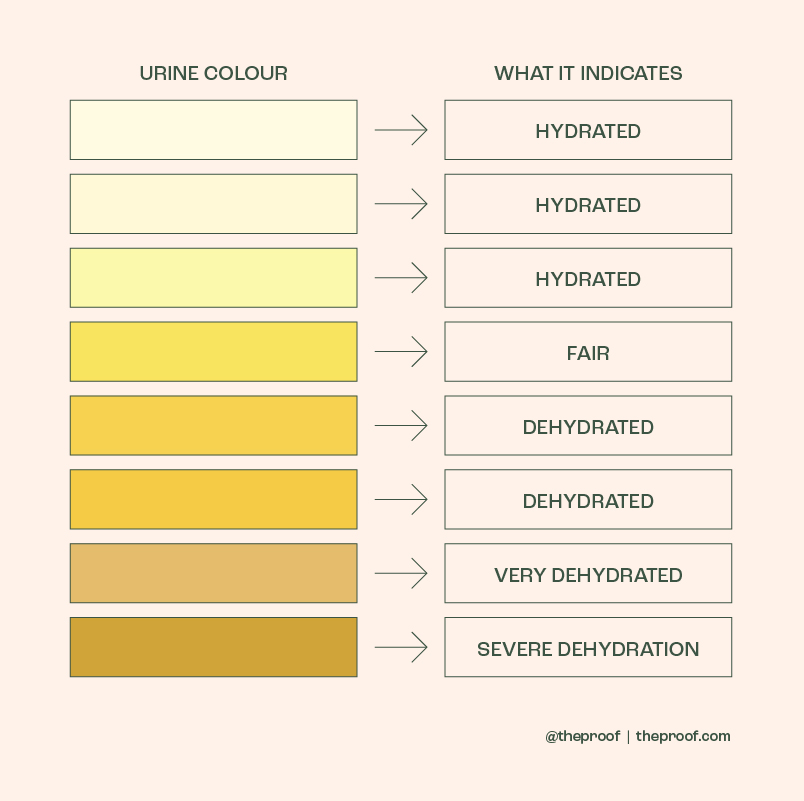

- After your workout, rehydrate with this same solution over the course of several hours. One indicator of how well you rehydrate is how you feel the next morning. If you wake up very thirsty and with dark yellow urine, you probably didn’t rehydrate enough.

- If you’re working out or competing for more than 2 hours, use a food source of energy and keep the fluid focused only on rehydration.

I love this recommendation for its simplicity and practicality. As Dr. Sims says, each individual’s needs are unique and highly situation dependent. Other considerations include (5):

- Gender – women’s hydration needs are different from men’s and fluctuate with their cycle.

- Environment – heat, humidity, elevation, and how well you are adapted to your environment.

- Overall fitness – new exercisers are less adapted to the physiological changes that take place during a workout.

- Lifestyle factors – alcohol, smoking, and diet all influence hydration.

- Intensity of exercise – how much you sweat will influence water losses and subsequent rehydration needs.

- Length of exercise – workouts, athletic events, or competitions that are more than 2 hours will require additional fuel.

- Type of fluid loss – losing fluid in sweat is very different than losing fluid from diarrhea/vomiting.

Depending on the type, intensity, and length of your exercise sessions, you may need to consider additional electrolyte replacement. The more you sweat, the more electrolytes you lose, especially sodium. Sodium is essential to maintain blood volume and prevent excess fluid loss through urine. If sodium becomes depleted through excessive sweating or long sweat sessions, you’ll need to replace it to return to a normal fluid volume.

New research is finding that higher intakes of sodium in a rehydration beverage do a better job of maintaining blood volume and preventing excess urine output. A recent study examined the effects of a low carbohydrate, high sodium beverage (2.6% CHO and 45 mm/L sodium) with a high carbohydrate, moderate sodium beverage (6% CHO and 20 mm/L sodium) on athletes who lost 2.6% body weight after exercise. Those who consumed lower CHO and higher sodium were better hydrated sooner and lost less fluid in urine. (6) The higher your losses, the more essential optimal rehydration becomes.

Monitoring your individual fluid status and adjusting your hydration accordingly is the best way to provide optimal hydration. You may have heard to watch urine color to know if you’re drinking enough, and that can be useful to a point. But if you want to maximise your workout gains, you may be leaving results on the table if all you do is chug water and pee a lot.

A simple way to monitor and adjust your hydration is using the WUT method. (6) WUT stands for Weight, Urine, and Thirst.

- Weight – assessing your body weight before and after a sweaty workout provides an indicator of fluid loss, though there are other factors that influence weight changes, making weight loss a poor stand-alone indicator. Aiming for ~1% weight loss is optimal. You’re not going to be able to prevent fluid loss altogether. It’s a normal part of exercise. The goal is to prevent it from affecting your performance and then rehydrate afterward.

- Urine – monitor your urine color, with dark yellow indicating dehydration and pale yellow indicating positive fluid status. See the graphic below to get a visual for comparison.

- Thirst – while your thirst isn’t always the best indicator of whether you need water, in combination with the other indicators, it can guide your intake.

Taking these three metrics together gives a more complete picture of how well you’re hydrated before, during, and after your workouts. Being optimally hydrated, not over or under, allows for peak performance and maximal gains. If you find you’re struggling in your workouts or feeling depleted afterward, troubleshooting your fluids might be the place to start.

I recommend playing around with what hydration method works best for you. Some people lose a lot of salt in their sweat, while others don’t. Your level of adaptation to heat and intensity also plays a role in how much fluid and sodium you lose. The type of workout you do, how long it is, how much you sweat, and how you feel while you’re exercising will guide you in choosing the optimal hydration and rehydration formula. There’s not one right answer for every individual and every exercise situation.

These days, I’m doing experiments of my own to find what hydration methods allow me to hit it hard in the gym and recover well afterward. I’ve recently been trying out ⅓ a sachet of LMNT mixed in 2 cups of water as my post-workout drink, which I typically have at the same time as a carbohydrate and protein rich meal.

LMNT is formulated for anyone with high electrolyte loss who’s interested in leveling up their athletic performance. It’s compatible with a whole food, plant rich dietary pattern as well. To try it for yourself. Go to www.drinklmnt.com/simon

You’ll also receive a free LMNT Sample Pack with any order which is pretty great.

As always, it’s fascinating to dive deep into these health topics to enhance our understanding of how we can support our body for optimal health.

– Simon

References:

- The Hydrating Effects of Hypertonic, Isotonic and Hypotonic Sports Drinks and Waters on Central Hydration During Continuous Exercise: A Systematic Meta-Analysis and Perspective PMID: 34716905

- Fate of ingested fluids: factors affecting gastric emptying and intestinal absorption of beverages in humans PMID: 26290292

- Absorption of glucose, sodium, and water by the human jejunum studied by intestinal perfusion with a proximal occluding balloon and at variable flow rates PMID: 5552186

- Physiology and pathophysiology of splanchnic hypoperfusion and intestinal injury during exercise: strategies for evaluation and prevention PMID: 22517770

- Optimal composition of fluid-replacement beverages PMID: 24715561

- Post-Exercise Rehydration in Athletes: Effects of Sodium and Carbohydrate in Commercial Hydration Beverages PMID: 38004153

- Relationships Between WUT (Body Weight, Urine Color, and Thirst Level) Criteria and Urine Indices of Hydration Status PMID: 34465235