While the scientific consensus (major guidelines from organisations such as AHA, ACC, EAS and ECC) clearly recommends restricting saturated fat to 5-10% of total calories to lower our risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD), there is a group of people who continue to proclaim that saturated fat has been unfairly demonised. By and large, these folks follow a low-carbohydrate diet rich in animal products and place an enormous amount of weight on anthropology (what our ancestors ate). It makes complete sense they want to defend saturated fat. Although they don’t have to be, typical low-carbohydrate diets are rich in animal products, particularly red meat, making it almost impossible to stay under the previously stated saturated fat recommendations—even when eating lean organic meat (we’ll come back to this).

Rather than reiterating the guidelines for a healthy heart and showing the vast number of studies that led these highly reputable organisations to their recommendations, I want to spend some time looking at the major pieces of evidence that my low-carb friends use to defend saturated fat. What is it that has them convinced we should be doubling down on T-bone steak and suet, going against the consensus? Perhaps they have a case after all.

First, before we take a look behind the curtains, I have simply listed the pieces of evidence so you are familiar with each of them.

For ease of review, I have split the evidence commonly used to defend saturated fat into these categories:

1 – Anthropology

- There is no specific piece of anthropology but rather a general rhetoric that because there is evidence of early humans eating meat, it should therefore be considered a crucial part of our diet today. The claim here is that “the foods we evolved on must be the best foods for us today”.

2 – Observational studies (including meta-analyses)

- Observational evidence from Indigenous populations: the Polynesians and the Maasai consume high amounts of saturated fat) and appear to have low incidence of CVD. The claim here is that certain Indigenous populations, such as the Polynesians and the Maasai, consume a lot of saturated fat and have low risk of CVD.

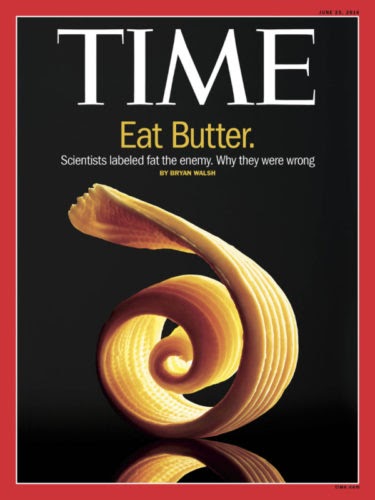

- The French Paradox: the claim here is that the French have a relatively low incidence of coronary heart disease despite consuming a lot of saturated fat.

- There are also a few widely cited meta-analyses that have looked at observational studies to determine if eating higher amounts of saturated fat places one at higher risk of developing CVD. The most commonly cited of these are the Siri-Tarino Meta-Analysis (2010) and Chowdhury Meta-Analysis (2014), which together famously resulted in the 2014 TIMES magazine cover “Butter is Back”. The claim here is that meta-analyses show people eating more saturated fat are not at higher risk of CVD.

*The Chowdhury Meta-Analysis included both observational studies and RCTs.

3 – Clinical intervention studies

- Minnesota Coronary Experiment (1968): often cited via the Ramsden 2016 re-analysis of this study

- Sydney Diet Heart Study (1966): often cited via the Ramsden 2013 re-analysis of this study

Both of these studies are Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs) conducted in the late 1960s to the early 1970s that investigated whether reducing saturated fat in one’s diet would lower risk of dying from coronary artery disease (the most common type of heart disease globally).

The claim made here when citing these studies is that “In the only long-term clinical intervention studies, reducing saturated fat did not reduce risk of dying from coronary artery disease, and thus, the traditional diet-heart hypothesis is flawed”.

Of course, this list of studies is by no means exhaustive, and I am more than happy to add in further studies at a later point in time. However, based on what I have come across, these are by far the most common pieces of evidence used to suggest that the guidelines recommending we limit saturated fats are wrong.

The Anthropology Argument for Saturated Fat

Sure, what our ancestors ate hundreds of thousands of years ago (even millions of years ago) makes for an interesting story. But should what Homo erectus georgicus or Homo habilis ate 2 million years ago guide our food decisions today? I mean, admittedly, as is the case for all of us, I wasn’t there, so I can’t exactly prove it, but I do have a hunch that they weren’t exactly eating for longevity. Instead, from an evolutionary perspective, it would seem they were eating for survival—to get through to the next day and make it to an age to procreate. Even if they were fortunate enough to have the nutrition science we have today, it’s very unlikely Homo Erectus had the same food availability and thus choices that we have. When food is scarce, it doesn’t really matter if meat raises your cholesterol! It’s better than starving.

If that’s not enough for us to see how illogical this idea of eating like our very distant ancestors to achieve good health in 2021 is, then what about how speculative this information is? While it’s true that our ancestors ate meat, they also ate plants. How many plants and how much meat? That’s greatly debated. While some argue meat was responsible for the development of our brain, which separates us from early hominins, others argue it was tubers and other plants. Others again argue it was simply Homo erectus’ discovery of fire, unlocking calorie-dense foods (both meat and tubers) and allowing our bodies and brains to grow. Just like today, there probably wasn’t one diet, with early humans eating according to the food available in their location across the seasons. The point is not who is right or wrong here but that no matter which way you lean, towards meat or plants, the eating patterns of early humans are highly speculative. This is why the guidelines, from organisations such as the American College of Cardiology (as mentioned above), are making their recommendations to the people of 2021, who want to live into their 70s, 80s and perhaps beyond, from data on modern-day humans, not Homo erectus.

Sidebar: One of the reasons why meat has been perhaps overstated in our ancestors’ diet is that while bones survive underground over centuries, plant remains do not. As such, when digging up stone age sites, there is likely to be very little evidence of the plants being consumed by the people from that area. This of course can lead to a bias towards concluding that our ancestors ate an animal-protein-based diet. However, in 2016, Yoel Melamed and his team examined a waterlogged site in Israel believed to be occupied by Homo erectus some 780,000 years ago which contained the seeds of 55 unique edible plants—mainly nuts, fruits, seeds, vegetables and tubers. It’s highly likely that in other sites around the world, humans were also eating a varied plant diet, but given that their remains perish unless miraculously preserved, archaeological excavations have only found bone remains.

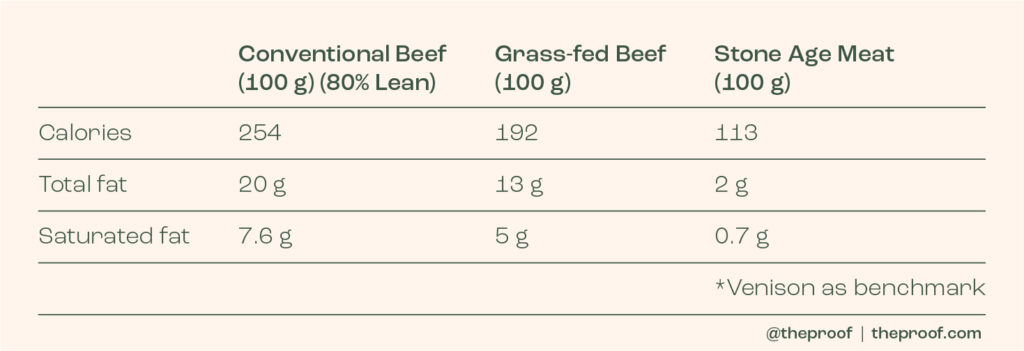

The last thing I want to say here is that even if we were to pretend that basing our food choices off what our very distant ancestors ate was an intelligent idea (which I hope I have shown is not), do we really believe Homo erectus was eating the same type of meat landing on most people’s plates today? The best records we have suggest that early humans likely caught wild animals like woolly mammoths, who have a nutritional profile that is nothing like that of a cow—be it organic or conventional. The closest meat today that would best approximate woolly mammoth would likely be something like venison (e.g. elk, deer, antelope). As you can see below, these meats are drastically lower in saturated fat compared to both organic and conventional beef.

The bottom line here is that I wouldn’t be putting too much stock into how Homo erectus did or didn’t eat! It really shouldn’t concern us when we live in a completely different time and have completely different goals. While we want to live into our 70s, 80s and beyond, in good shape and without chronic disease, Homo erectus wanted to survive until the next day. Furthermore, when Homo erectus was successfully able to catch an animal, its nutritional properties would have been vastly different from the meat that 99% of people are eating today—be it organic, regenerative or conventional.

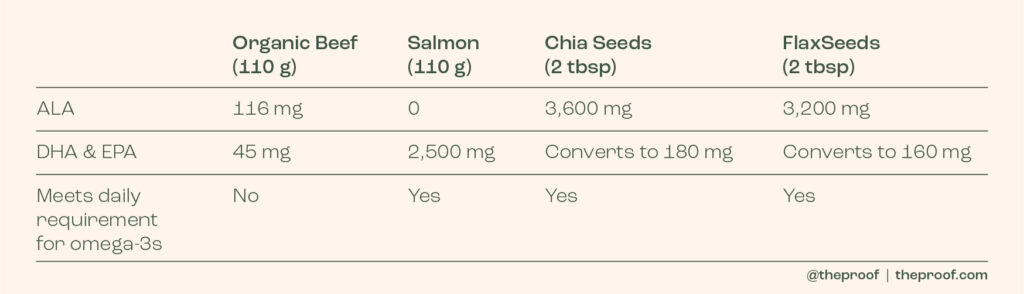

Sidebar: I find it odd that certain people hype up the omega-3 DHA/EPA content of organic beef. The common claim is that “organic meat contains twice as much omega-3s as conventional”. Unfortunately, given conventional meat is so low in omega-3s, this is hardly something to write home about. The amount of omega-3s in a serving of organic meat is quite literally a drop in the ocean when it comes to your health. People would be far better off consuming fatty fish or plant-based sources of omega-3s such as chia or flax seeds. I’ve broken this down below to show how silly this is!

*Of course, we don’t eat just one single food, so I am well aware that you can eat beef within a diet that contains ample amounts of omega-3s. I am simply showing that we really shouldn’t be building it up as some sort of omega-3 superstar when it’s clearly not.

Indigenous Populations and Saturated Fat Intake

The next argument often used to defend saturated fat is pointing to populations that consume a high amount of saturated fat and that have a low incidence of CVD. As opposed to anthropology, I am not against using observational studies to help us piece together the nutrition science puzzle. While it’s widely understood that observational studies cannot prove causation, when performed well, they are able to test certain questions that are just not feasible with clinical trials. So, we cannot just discard this research because it’s ‘epidemiology’—we need to look into it. The three most common populations that I see being cited to defend saturated fat are the Inuit, the Maasai and the Polynesians.

The Inuit

Since a pair of Danish researchers, Bang and Dyerberg, undertook 6 expeditions to Greenland, it has been thought that the Inuit of Greenland rarely experienced CVD. Given that their diet was made up of almost entirely animal products with an absence of fruits, vegetables and many important nutrients, this finding went against everything we know about heart disease and nutrition. The theory was that despite their animal-based diets, the Inuit were protected from CVD by the high level of omega-3 fats in their diet from the whale and seal flesh they were eating. However, when researchers set out to verify the original ‘findings’ some 40 years later, which were based mostly on clinical observation and x-ray (hardly reliable measures of atherosclerosis), they found that there was not any evidence of lower rates of CVD amongst the Inuit. In fact, it’s been documented that compared to non-Eskimos from nearby populations, the Inuit actually have the same risk of heart disease, twice the risk of stroke and a shorter life expectancy of approximately 10 years. Studies going back over 1,000 years have also reported the presence of heart disease in frozen Eskimo mummies.

What’s the most interesting thing? The health of this Inuit population has actually improved in more recent decades as they have adopted a more Western diet. That says something about their original diet.

All in all, this is hardly data we can use to justify the consumption of unlimited amounts of animal fat. The idea that the Inuit were protected against CVD is based on very poor records and if anything appears to be completely false.

*Note: I have since learned that describing the Inuit of Greenland as ‘Eskimo’s’ can be offensive and a form of racism. As a result I have edited this entry and encourage you to read up on this topic here if you’d like to understand more.

The Maasai

The Maasai are a tribal population from Northern Tanzania and Southern Kenya who reportedly consumed an almost exclusively animal-based diet, focussing on meat, dairy and blood, and had very low risk of CVD. However, when this research was published in the 1960s, the researchers acknowledged it was incredibly hard to determine what people were eating. Furthermore, their assessment of heart disease was very basic and likely led to under-diagnosis.

“The accurate measurement of dietary intake of these people proved extraordinarily difficult. We were able to make only limited measurements. This difficulty is because of the erratic intake of food, there being no fixed meal patterns in the families, because there are no uniform units of measurement or utensil and because of the disruption of usual behavior in the presence of an observer.” (Mann et al. 1964)

In 1986, a slightly more thorough assessment of their diet and lifestyle was performed revealing that their diet was in fact less focussed on meat than initially thought, although it did contain substantial amounts of milk, and it is thought the men’s diet likely differed considerably to that of women and children. There are a few really important things to understand about this population:

1 – They were in what seemed to be an enormous calorie deficit (25-50% fewer calories than their maintenance level), a result of constant movement. In fact, in order to expend a similar amount of energy, the average Western person would need to walk an extra ≈19km per day. On average, the Maasai are said to expend around 2,565 calories above their BMR (basal metabolic rate)—this is an extremely high amount of daily energy expenditure! The circumstances of the Maasai are completely different from eating meat and dairy within the context of a Western world where people eat excessive amounts of food and lead sedentary lifestyles.

2 – In addition to borderline starvation, the Maasai were known to consume a lot of plant medicines, herbs and spices associated with cholesterol reduction. They were, and still are today, also prone to parasitic infections which again are associated with cholesterol reduction. These parasitic infections are likely the result of drinking unpasteurised milk and undercooked meat.

3 – Although initial reports suggested they didn’t have heart disease, more recent autopsies suggest that is not true with many having severe atherosclerosis. Interestingly, however, it seems their extraordinary physical activity levels resulted in widening of their arteries—making them less likely to suffer from blockages despite the plaque build-up.

4 – Unlike extremely validated populations, such as the Seventh Day Adventists from the AHS-2 cohort, there is a lack of validated data from the Maasai population detailing what they ate, what diseases they suffered from, how long they lived and ultimately what caused them to die. In this validated AHS-2 population of people living in Canada and California, who live lifestyles more similar to ours than the Maasai tribe, men who eat less animal products are at significantly lower risk of dying from CVD:

- Vegan men – 42% lower risk of dying from CVD

- Lacto-ovo vegetarian men – 23% lower risk of dying from CVD

- Pescetarian men – 44% lower risk of dying from CVD

This data is from a cohort of 96,469 men and women recruited between 2002-2007 who have since been followed for 1-2 decades.

The Polynesians

The Polynesians are a group of people who live across 1,000+ islands about 8,000 km east of Australia. This is perhaps the most interesting example of a group of people who tend to eat a higher-fat diet and have less CVD than Western populations. Various studies looking at Polynesians from islands such as Tokelau and Pukapuka have shown that they get around 50% of their calories from fat, with most of this coming from coconut flesh (which is 90% saturated fat). This brings me to something that is often overlooked in nutrition science: compared to what? Sure, the Polynesian diet, which prominently features coconut products within a diet that features a good amount of fibre, fruit and fish, and a tiny amount of processed food, is better than a Western diet rich in both saturated fat and refined carbohydrates. I would agree with that. In fact, we know when Polynesians migrate to NZ and decrease their saturated fat intake in exchange for more calories from more ultra-processed foods rich in refined sugars, their risk of CVD goes up. But this is to be expected—swapping saturated fat for refined carbohydrates is at best a lateral move. Whereas, swapping saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat (fish, nuts, seeds, etc.) or unrefined carbohydrates (whole grains) reduces CVD risk.

What we can’t say is that because Polynesians who migrate to NZ and eat less saturated fat have higher risk of CVD, this justifies a high consumption of saturated fat from meat, dairy, etc. All it tells us is that their native diet rich in coconut products, fruit and fish, with good amounts of fibre, is better than a Western diet.

We also don’t have the data to see if Indigenous Polynesians would have lower risk of CVD if they ate less coconut meat. However, based on the data we do have from clinical trials around the world, it would be highly likely that yes, if Polynesians ate more unsaturated fats and less saturated fat from coconut meat, their risk of CVD would decline.

We should also be careful when using the Polynesian diet to advocate for the consumption of coconut oil. As described above, it’s highly likely they would be at lower risk of CVD without coconut products in their diet and, more importantly, weren’t consuming coconut oil. They were consuming coconut meat, and the best evidence we have available on coconut oil, a 2020 meta-analysis of 17 trials, published in the prestigious Circulation journal, shows it significantly raises LDL-C and thus is likely to place one at increased risk of CVD. Their conclusion is “Coconut oil should not be viewed as healthy oil for CVD risk reduction, and limiting coconut oil consumption because of its high saturated fat content is warranted.”

The French Paradox

When researchers first described the French Paradox in 1980, it was met with great enthusiasm. Imagine uncovering that our favourite foods, against all the science of the day, were actually healthy for us! Finally, solid science that suggested we should double down on our meat and dairy consumption. Specifically, three French researchers found that despite their relatively high saturated fat consumption, French men had lower risk of developing coronary heart disease than would be predicted by what was observed in at least 40 other countries. However, there are two KEY problems with their interpretation of the data.

1 – The most significant problem is that the idea of the French Paradox was formed from cross-sectional data (data from one point in time rather than data collected over time). We know that chronic diseases like coronary heart disease are insidious—the pathophysiology bubbles away under the surface for decades until it reaches a point where one becomes symptomatic and is diagnosed. Importantly, unlike the other areas that the researchers were comparing the French to, mainly other European countries and America, the French had only recently increased their consumption of animal fat (they increased their consumption of animal fats by around 30% between 1970-1980). Thus, as a team of researchers noted, “the difference is due to the time lag between increases in consumption of animal fat and serum cholesterol concentrations and the resulting increase in mortality from heart disease—similar to the recognised time lag between smoking and lung cancer.” Put simply, they hadn’t been eating a high-animal-fat diet long enough for it to affect their death rates from heart disease.

2 – The second problem is that at the time of the study, French doctors did not always properly classify deaths from ischemic heart disease correctly.

Together, we are left with a very consistent pattern from 40+ countries that clearly show high consumption of animal fat is associated with greater risk of ischemic heart disease and an anomaly in France that appears to boil down to the way data was collected and interpreted. I’m not sure how anyone can cite this in good faith, as reliable evidence to argue that saturated fat has been wrongly vilified, particularly given the data we have from RCTs that we will cover shortly.

The Siri-Tarino and Chowdhury Meta-Analyses

When it comes to causing confusion over the role of saturated fat in CVD, both of these meta-analyses are major culprits.

Firstly, it should be said their conclusions are in direct contrast to the wider body of literature on saturated fats, including multiple meta-analyses that only included RCTs (higher in the evidence hierarchy), that show clear benefit to reducing saturated fat. You can view those here and here.

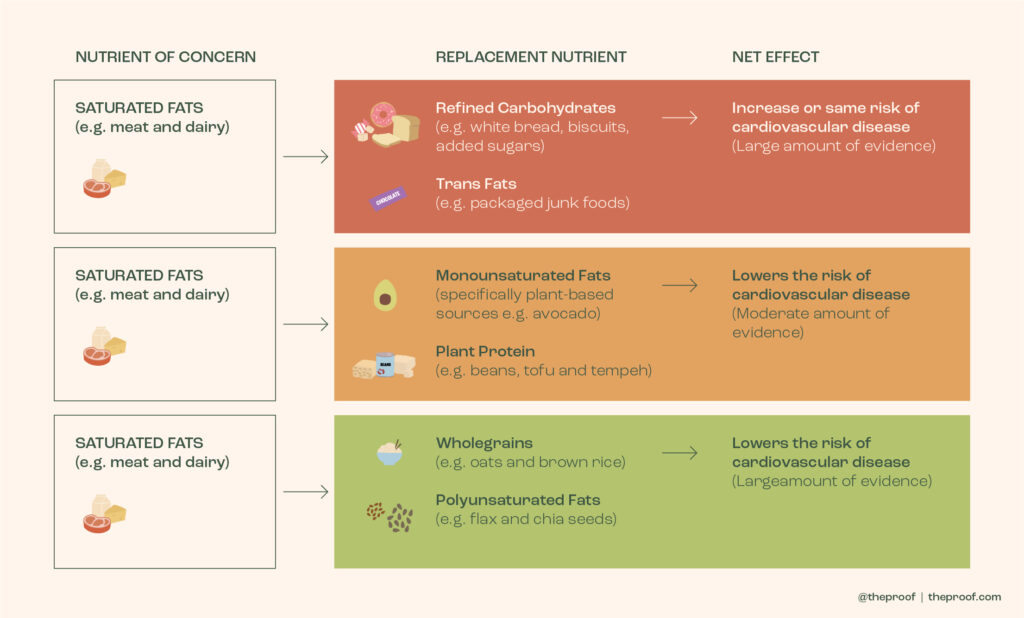

The major problem with the Siri-Tarino and Chowdhury meta-analyses is that they failed to consider the replacement nutrient in their analysis and recommendations. We know when someone swaps calories from saturated fat directly for refined carbohydrates (e.g. sugars in biscuits, cakes, etc.) their risk of CVD either stays the same or even increases. In other words, if you look at what happens when you swap meat for Oreos, you can make saturated fat look good! But there are other options.

As you can see below (an image I have put together based on the results of a wide body of observational studies and RCTs), what someone replaces saturated fat with determines how their risk of CVD changes! If people swap foods rich in saturated fat (beef, full-fat milk and cheese, etc.) for foods rich in polyunsaturated fats, unrefined carbohydrates or even plant protein (fish, nuts, seeds, whole grains, legumes, etc.), their risk decreases.

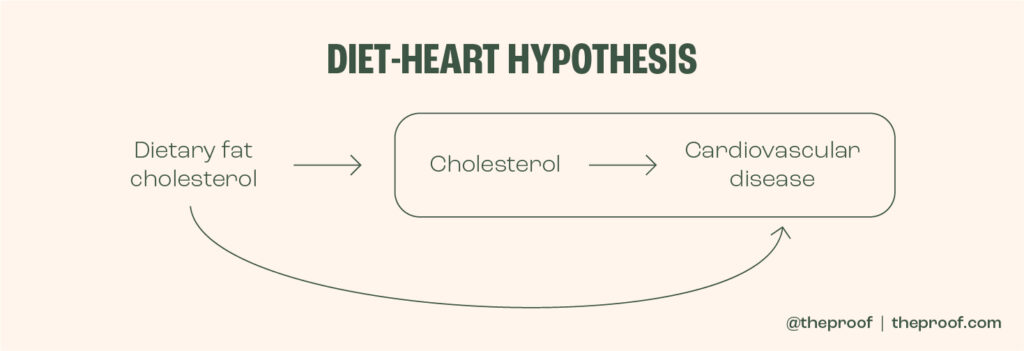

The next issue was specific to the Chowdhury meta-analysis. To understand this issue, we need to take one step back and understand what the diet-heart hypothesis is. I’ve illustrated it below. Essentially, it is that saturated fat (and to a lesser degree, dietary cholesterol) raises LDL cholesterol levels which then results in damage to the artery wall and atherosclerosis (plaque build-up and narrowing within an artery, making it susceptible to becoming blocked).

Roughly 50% of the trials included in the Siri-Tarino and Chowdhury meta-analyses controlled for serum (blood) cholesterol levels in their analysis. What this means is that they only compared subjects with other subjects who had the same cholesterol levels. Given we know from hundreds of feeding trials that saturated fat raises cholesterol levels, this adjustment makes no sense. If you only compare people with comparable cholesterol, you are essentially removing the variable, and mechanism, believed to be responsible for an increased risk of CVD. This is called over-adjustment.

A third issue, specific to the Chowdhury meta-analysis (there were many issues with this particular paper, which resulted in it having to be republished), was that when you remove the Sydney Diet Heart Study (a flawed study we will chat about below), there was actually a 19% reduction in coronary artery disease. And this isn’t just conjecture, when the paper was republished, with corrections made, swapping saturated fats for polyunsaturated fats was shown to significantly reduce one’s risk of coronary artery disease. Unfortunately, Time magazine had already published “Butter is Back”, and thus, a lot of the damage was done—people love to hear good things about their bad habits. Who doesn’t want to double down on butter and red meat and improve their health at the same time!? For a full breakdown on the issues with the Chowdhury meta-analysis, you can read the various comments sent into the Annals of Internal Medicine (the journal that published the paper) from a range of doctors and scientists across the world.

Unsurprisingly, even one of the authors of the Chowdhury meta-analysis, Dariush Mozaffarian of the Harvard School of Public Health, expressed his concern over the findings:

“Personally, I think the results suggest that fish and vegetable oils should be encouraged,” he says. But the paper was written by a group of authors, he points out. “And science isn’t a dictatorship.” – Science Mag

The bottom line here? When science is performed properly and we consider the nutrient replacement, there is a clear argument for swapping foods rich in saturated fat (mainly meat and full-fat dairy) for fish, nuts, seeds, whole grains and legumes. All of this is well summarised by a 2018 review published in the British Medical Journal that you can read here should you want to dive deeper.

Clinical Intervention Trials

Okay, so if all of the above is true and whether or not saturated fat is harmful or not comes down to what it’s replaced with, why are there two trials that seemingly show this is not in fact the case? I’m talking about the Minnesota Coronary Experiment and the Sydney Diet Heart Study—two studies from the late 1960s that randomised subjects to one of two groups: a group consuming high amounts of saturated fat or a group consuming less saturated fats, instead replacing those calories with polyunsaturated fats.

To preface this, it’s important to remember that in addition to the re-published Chowdhury meta-analysis (mentioned above), both a 2010 and 2020 meta-analysis of RCTs looking at what happens when you swap saturated fat for polyunsaturated fat clearly show this dietary change results in a reduction in risk of developing heart disease. Specifically, the 2020 Cochrane Meta-Analysis, which included 15 RCTs, found a 27% lower risk of cardiovascular events (heart attack, stroke, etc.) when swapping saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat. They also found a 16% reduction in risk of cardiovascular events when swapping saturated fat with carbohydrates, presumably unrefined. This really should be all one needs to put down the steak in favour of fish or legumes—3 meta-analyses all showing the same thing. I can’t quite get my head around why anyone would want to dispute this. However, it seems certain people do. Because folks still look past these meta-analyses and instead point to the two single trials that support their position. I’m going to take a closer look at them with you.

It’s important to understand that these studies started in the late 1960s when we didn’t have anywhere near the information we have today on the role of diet in the development of heart disease. As such, several of the problems with these studies are through no fault of the researchers but just a by-product of operating during a time when we knew much less.

Sydney Diet Heart Study:

- This trial included 458 men with coronary artery disease (secondary prevention trial).

- Subjects were randomised to a control group or a group that consumed polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat (< 10% of calories from saturated fat).

- Specifically, the intervention group replaced saturated fatty acid with linoleic-acid-rich (omega-6-rich) safflower oil.

- The subjects in the intervention group were given a safflower oil margarine that we now understand (thanks to more research since the 1960s) would have contained dangerous trans fats. This is what the AHA specifically said in their latest Presidential Advisory paper on dietary fats and CVD: “The Sydney Diet Heart Study showed that using a margarine rich in trans unsaturated fat to replace saturated fat increased CHD events, confirming similar adverse results in epidemiological studies.” Pointing to this to support a diet rich in saturated fats is very disingenuous. Not only is it cherry-picking, a single study that has a conclusion that is contradictory to higher levels of science (meta-analyses of RCTs), it is also a fundamentally flawed study.

Minnesota Coronary Experiment:

- Subjects were recruited from mental health hospitals and randomised to one of two groups: a control group or an intervention group (polyunsaturated-fat group).

- The intervention group replaced saturated fat with linoleic-acid-rich (omega-6-rich) corn oil.

- 10,000 patients needed to be followed for 3 years in order to have enough statistical power. The study enrolled 9,423 subjects and lost 75% of them in the first year. As a result, it lacked the statistical power to show any sort of meaningful result.

- Although it was considered an RCT, subjects were allowed to leave the mental health facility, and what they ate outside of the hospital wasn’t tracked. So, technically, it’s not a true RCT.

- Like the Sydney Diet Heart Study, subjects in the Minnesota Coronary Experiment intervention group were given a corn oil margarine that we now understand would have contained dangerous trans fats that increase one’s risk of CVD. Even if the study was sufficiently powered, the inclusion of trans fats in the intervention group clearly makes it impossible to determine if replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat affects one’s risk of CVD.

For all of the above reasons, both of these trials have been widely condemned and are considered by the likes of the AHA as unreliable.

So, where does this leave us?

- Anthropology is interesting but highly speculative. Plants in our ancestors’ diets have likely been hugely understated due to the fact that plant remains do not stay preserved like bone remains do. Regardless, basing our dietary choices off of what Homo erectus ate at a time when he quite literally just wanted to survive until the next day seems odd given today, we live in a different environment, and very likely have different goals (e.g. living into our 70s, 80s and beyond in good health). Be careful of low-carb enthusiasts who are obsessed with anthropology and the ‘ancestral way of life’. It’s a distraction from what matters most to your health.

- Data on the Inuit, Maasai and Polynesians are interesting but not well-validated. Given we have much more validated and higher levels of evidence to base our dietary decisions on, these simply cannot be used to defend saturated fat. Well-validated observational studies clearly show that when we swap saturated fat for polyunsaturated fats, monounsaturated fats, whole grains or plant protein, people reduce their risk of CVD. In a 2017 meta-analysis of observational studies, vegetarians were shown to be at 25% lower risk of heart disease compared to meat-eaters. This finding is supported by one of the longest RCTs we have looking at dietary intervention and CVD events in people at risk of CVD, the PREDIMED trial. The PREDIMED trial showed subjects adopting a PRO-vegetarian Mediterranean diet had 41% lower risk of premature death compared to controls who ate a diet higher in red meat and refined carbohydrates. Essentially, this is a very plant-predominant Mediterranean diet. Think lots of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds and olive oil with just modest amounts of animal products, mostly fish.

- The Sydney Diet Heart Study and Minnesota Coronary Experiment are both difficult to use for dietary recommendations given the inclusion of trans fat margarine in the intervention groups which makes it impossible to know the effect that eating polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat would have had on their subjects’ CVD risk. Furthermore, the Minnesota Coronary Experiment wasn’t really a true RCT and lacked the power to find any sort of statistically significant result anyway. Fortunately, we have three well-powered meta-analyses that show when you replace foods rich in saturated fat with those rich in polyunsaturated fat, you significantly reduce your risk of CVD. This is the highest level of evidence we have today and should therefore be what we use to make public health recommendations. Additional research suggests swapping saturated fat for monounsaturated fat, whole grains and plant protein also lowers risk of CVD, albeit less than swapping for polyunsaturated fats. Hence, this is why the AHA, ACC, EAS and ECC all suggest limiting saturated fat intake to 5-10% of total calories. What’s the easiest way to do this? If you ask me, not counting grams of fat! I think it’s easier to just eat more plants and less animal products, and naturally, your saturated fat intake will take care of itself and fall below 10% (pending you’re not guzzling down coconut or palm oil). Replacing red meat with legumes and/or fish, and full-fat dairy with low-fat dairy or plant-based milks, are two great places to start.

To learn more about nutrition, check out my podcast where I regularly sit down with doctors, scientists and other experts to help you make sense of the science and upgrade your health by making positive changes to your plate. To order my book The Proof is in the Plants head over here.

The best way to support the podcast is to use the products and services offered by our sponsors. To check them out, and enjoy great savings, visit theproof.com/friends.